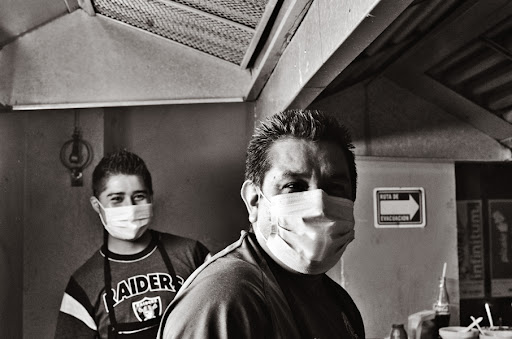

When I arrived in Mexico on a warm night in the spring of 2010, the city felt frighteningly large. I knew the streets, but the fleeting familiarity of darkened corners hardly dispelled a creeping sense of isolation. That is, until I arrived at a particular corner where orange light and sweet charcoal smoke spilled out of a small door onto the sidewalk. I had been a regular at this taco stand in 2008, when I lived a few steps away. As I stepped inside, Rodrigo looked up and paused, recognition flickering across his face. 'Güero!' he exclaimed, 'where have you been?'

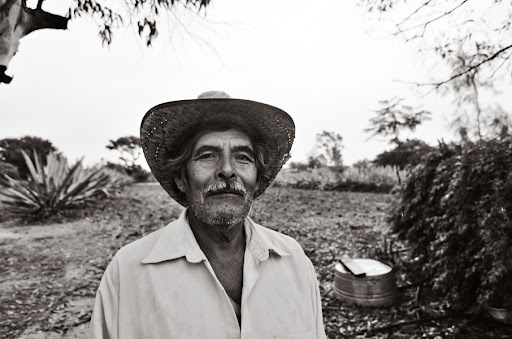

Over the next sixteen months I again became a weekend regular at Tacos Nena, often arriving at 7:30, just as Rodrigo began to slice chorizo and pile the grill with chicken thighs. Behind the facemask that he grudgingly wore, a knowing smile glimmered in the corners of his eyes. Usually, we discussed fútbol, since he had convinced me to become a Pumas fan, as he was. Genaro, his father and a Chivas fan, frequently sniped--in nearly incomprehensible Spanish that moved through my ears in a blur--that everyone knew which team was really the best. On evenings when the anonymous loneliness of the city closed around me, it was a fluorescent-lit refuge.